They say "an elephant never forgets," but SPH-B faculty member Daniella Chusyd, Ph.D. is about to put that theory to the test.

An assistant professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, Chusyd’s innovative research on what elephants can tell us about healthy aging earned her a place at the National Academies of Medicine (NAM) Emerging Leaders Forum that took place last spring, thanks to a nomination by David Allison, former dean of SPH-B and current NAM member.

"Having this prestigious accolade from the academies provides some legitimacy to my research while also raising the profile and validity of using elephants as a comparative approach to pushing human healthy aging research….as a comparative species it could add new information," says Chusyd. "I appreciate David’s willingness to continually put me in positions to succeed."

During the forum, Chusyd had the opportunity to witness different fields of research that could potentially support or add a new dimension to her own current research.

"There was a large section that was about the One Health Initiative, which is the concept that human and animal health—including wildlife as well as livestock and domesticated pets and environmental health—is all interconnected," says Chusyd. "You can’t view them as silos anymore, which public health has historically done, particularly prior to Covid-19."

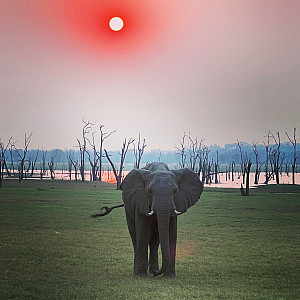

Chusyd has successfully developed a One Health undergraduate course for general education credit within the department, as well as a study abroad One Health field course in Kruger National Park South Africa, with plans to develop a One Health graduate level course in the near future. Thanks to a $15,000 grant from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CTSI), Chusyd will travel to Kafue National Park in Zambia, Africa with Provost Professor Jonathon Crystal, Ph.D. of the Indiana University Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences to study elephant tumor suppressor gene TP53 variation, as well as cognitive function, as a comparative approach to human cognitive aging.

"We are trying to determine if elephants can remember what, where, and when—and for how long do they remember it—by using scent," says Chusyd. "We will use a device to put out some novel smells, get the elephants used to it, and see if they remember that this is a place that has a novel smell."

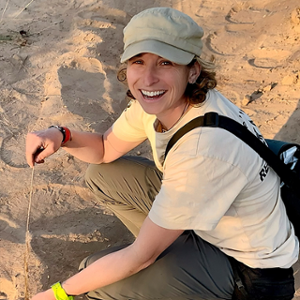

Photo courtesy Daniella Chusyd

The device, which was developed in partnership with on-campus PBS Machine and Electronics Instrument Shops and will be controlled by a laptop in the field, will dispense a compartment with the scent. When the elephant correctly identifies/remembers a scent, another button will drop down the food reward. Once the elephant departs, the device can close securely to ensure safety to the surrounding wildlife.

"We know that matriarchs in herds are typically elderly female elephants that are a repository of ecological and social knowledge for her whole family," says Chusyd. "What we don’t know is how she is picked. Is her memory superior to everyone else? Or does everyone in the herd have a good memory but she is also a good leader?"

Chusyd says using elephants as a comparative study to human health is not as far-fetched as it seems. Elephants and humans have comparable lifespans, similarly rely on complex social bonds, and there has been evidence of empathy in case studies showing that elephants bury their deceased young. In fact, Chusyd also studies how orphaned elephants and the stress of their life situation influence their pace of aging compared to wild elephants.

"We are getting in a lot of cool preliminary data, including using epigenetics clocks to determine whether this extreme stressor early in life accelerates their aging, so even if the individual is 20 years old, their body is functioning more like a 30-year-old," says Chusyd. "This upcoming academic year is really about building up this foundation of data and keeping our research going in Zambia for years to come."

For more SPH-B news, visit go.iu.edu/48bx.